Canada declared war on Germany on September 10, 1939, seven days after Britain and France. The first Canadian troops left for England in December. Although "obliged to go to war at Britain's side," the Prime Minister's delay of a week was a symbolic gesture of Canadian independence. As attention and efforts focused on the war in Europe, the Great Depression lifted.

Enlistment in the military soared, and manufacturing grew, in particular shipbuilding and aircraft construction. The value of production in the province essentially doubled over the six years of World War II. Indigenous peoples, along with Canadian residents of Asian descent and recent migrants, all enlisted to fight in the war, even though many were still not allowed to vote. In 1945, an Act to amend the Provincial Elections Act, 1945, allowed members of disenfranchised groups, if otherwise qualified, to vote if they had served in World War I or World War II. Industries traditionally closed to women, such as plywood, pulp, and paper mills, welcomed women's contributions to their workforce.

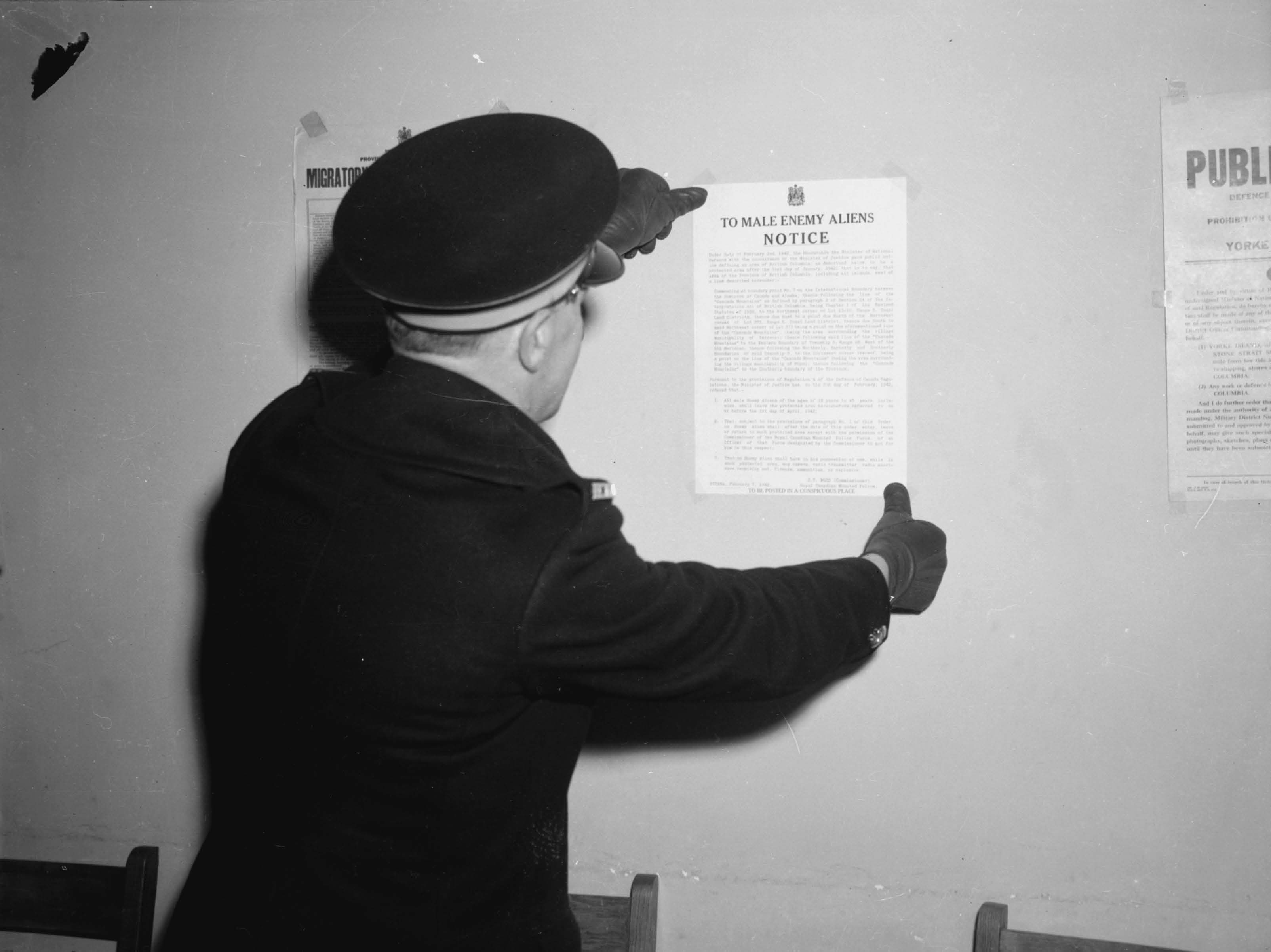

On December 8, 1941, one day after Japan attacked Pearl Harbour, wartime blackout measures went into effect all along the B.C. coast. Canada declared war on Japan shortly after and there was widespread fear that anyone of Japanese descent, in particular the coastal fishers who made up the majority of B.C.'s fishing fleet, might act against Canada's interests. Canada began seizing some 12,000 fishing boats belonging to Japanese Canadians and selling them off to mostly white fishermen.

In 1942, B.C.'s Japanese population of approximately 22,000 were forced into internment camps throughout the interior. More than half were Nisei, born and raised in B.C. In order to finance the internment of the Japanese Canadians and to permanently discourage them from returning to the coast, the federal government confiscated their agricultural property and personal possessions and allowed them to be auctioned off or sold at low prices.

When the war concluded in 1945, the federal government began to offer internees the choice of deportation to Japan or relocation east of the Rocky Mountains. Deportation was later cancelled due to public protest, but not before nearly 4,000 people had been sent to Japan, including many Nisei who had never travelled outside of Canada. On April 1, 1949, Japanese Canadians were given the right to vote and the legal restrictions used to control the movement of Japanese Canadians were removed.

No Japanese Canadian was ever charged with disloyalty, and the incident is now acknowledged as one of the worst human rights violations in B.C.'s history. In 1988, the Government of Canada formally apologized and offered compensation to Japanese Canadian survivors and their families.