On January 24, 1918, a by-election was held in the provincial riding of Vancouver City. Mary Ellen Smith, a prominent suffragist in British Columbia, received 58 per cent of the vote, becoming the first woman elected to the Legislative Assembly. Two weeks later, Smith arrived in Victoria to take her seat in the Legislative Chamber. One woman among 46 men, she was welcomed with a standing ovation. Flowers and congratulatory messages were delivered to her hotel. Among them was a note from the Local Council of Women:

"How delighted we are that you have been elected as representative of Vancouver City – truly a wonderful realization of our hopes, our dreams, and our labours of the past thirty-two years."

Mary Ellen Smith, the first woman elected to the Legislative Assembly

This pivotal moment in history marked the culmination of many decades of effort on the part of the province's suffragists.

The suffrage movement in B.C. had begun in earnest in the mid-1880s, with the capital city of Victoria an early hub for women's rights activists and suffrage campaigners. Some women in B.C. had been permitted to vote in municipal elections since 1873, but there was a growing sentiment among many that women's votes and voices were needed on the provincial stage – both as a matter of justice and also as a means of influencing the policies of the day.

Since the earliest years of the province's history it had been widely believed that women's roles in society should be limited to the domestic sphere. Women did work outside of the home, often out of economic necessity, but many faced low wages, poor working conditions and even violence. In addition to discrimination in education, women were considered by many to be less rational than men and of a different temperament – excuses often given to justify their exclusion from voting and public life.

Many women believed that securing the right to vote and be elected to public office would bring about needed improvements in women's and children's social and economic conditions. Early suffragists worked within various organizations, including local chapters of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) – the largest women's organization in Canada in the late nineteenth century.

The Victoria and Vancouver Island Council of Women, pictured at the Parliament Buildings in 1895.

Image F-02390 courtesy of the Royal BC Museum and Archives

The cause also received some early support in the Legislative Assembly, with a number of suffrage bills introduced by private members in the 1880s and 1890s. However, none of these bills passed second reading. Members of the WCTU and other suffragists also regularly petitioned the Legislative Assembly. While these efforts received some attention in the newspapers and helped raise the profile of the suffrage movement, successive provincial governments declined to act in their favour.

The early twentieth century saw an expansion in the number of groups campaigning for women's suffrage. The Victoria and Vancouver Island Council of Women – which had earlier fought for women to be elected as school trustees – turned their attention to suffrage on the provincial stage. In 1910, the Political Equality League was formed and soon had branches operating throughout B.C., organizing forums and debates and amassing thousands of signatures for petitions. The B.C. Women's Suffrage League emerged as a voice for working women, and both men and women in the labour movement provided key support for the cause.

In spite of this growing momentum, B.C.'s suffragists were still predominantly white and middle-class; in fact, the suffrage movement was marked by its remoteness from other groups in the province – notably First Nations and Asian women. Many suffragists viewed these women as potential beneficiaries of a progressive social agenda rather than political allies and equals.

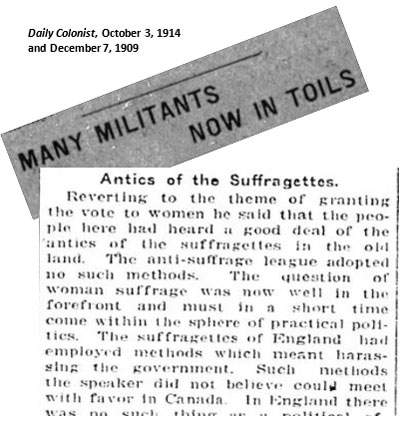

Like most other suffrage groups in Canada, B.C. suffragists largely chose not to adopt the more militant strategies used by the Women's Social and Political Union led by Emmeline Pankhurst in the United Kingdom. In fact, the activities of this branch of the U.K. suffrage movement often received coverage in provincial newspapers where the "antics of the suffragettes" were cast in a critical light. The suffrage movement in Canada focused more on strategies that involved speaking tours and events featuring prominent suffragists such as activist and author Nellie McClung.

With the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, suffrage groups channeled their efforts into supporting the war effort. By this time, many women were also contributing meaningfully to family finances and provincial revenues in B.C., providing an increasingly powerful rationale for giving women a voice in how the province was being run.

In January of 1916, Manitoba made history as the first province in Canada to grant women the right to vote and stand for election. Victories soon followed in Saskatchewan and Alberta, strengthening the B.C. suffragists' position and resolve. In September of 1916, Premier William Bowser agreed to hold a referendum on the issue in conjunction with the provincial general election. The referendum results revealed that 65% of the men who voted were in favour of extending the voting franchise to women.

In April of 1917, B.C. became the fourth province in Canada to grant women the right to vote in provincial elections and to run for provincial office. The following year, the federal Government in Ottawa passed similar legislation, enabling women to vote in federal elections and be elected to the Canadian House of Commons.

While this legislation signified an important step-forward for women's rights, it did not immediately result in universal suffrage for all people in B.C. For many, the path to suffrage took much longer owing to persistent racial, ethnic and religious discrimination.